When OpenAI released ChatGPT in November of 2022, educators understandably reacted with concern. Many were worried about the spread of misinformation, biased or discriminatory algorithms, and risks to student privacy. One of their most prevalent concerns was the fear that generative artificial intelligence (AI) and its ability to produce human-like writing would lead to a dramatic increase in cheating and plagiarism that teachers would be unable to detect or prevent.

While students did (and still do) misuse AI tools for school, our team worried about narrow public discourse that reduced AI tools to mere cheating machines. We found this discourse problematic for a few reasons. First, it painted a broad, deficit-based picture of students as dishonest and untrustworthy. Secondly, it fed into historical patterns of discipline disparity by race and gender, in which black and brown boys in particular are disproportionately punished in schools. Finally, our conversations with educators made us worried that fears of cheating would prevent them from teaching students the crucial AI literacy skills they need to succeed in a rapidly changing world. We worried that under-resourced schools would focus on bans and punishment (what one teacher we work with calls the “abstinence-only” approach to AI) while well-resourced schools would invest in training staff and teaching students to understand, evaluate, and use AI tools to enhance their learning.

Designing a research study

To address these challenges, we designed a study to understand how teachers and students defined cheating and learning with generative AI. We partnered with a group of 12 high school students from a linguistically diverse public charter school and 16 writing teachers from the Bay Area Writing Project. We presented them with four examples of how a hypothetical student might use ChatGPT to help them write:

Student A: Give me two possible first sentences for an essay arguing that schools should not require students to wear uniforms.

Student B: Make an outline with only headers and subheaders for me to use as I write an essay arguing that schools should not require students to wear uniforms.

Student C: Fix this paragraph I wrote arguing that school uniforms discourage students’ individuality. (*This prompt included a pre-written paragraph with grammatical and spelling errors.)

Student D: I am going to write an argument where I argue against mandatory school uniforms, but I am having trouble writing it. Please help me write my argument by taking the other side and giving me a list of counterarguments.

We instructed them to discuss the examples in pairs and then rank them independently according to how much they thought each student learned, and how much they thought each student cheated.

Participants had a range of conflicting views about cheating and learning with AI

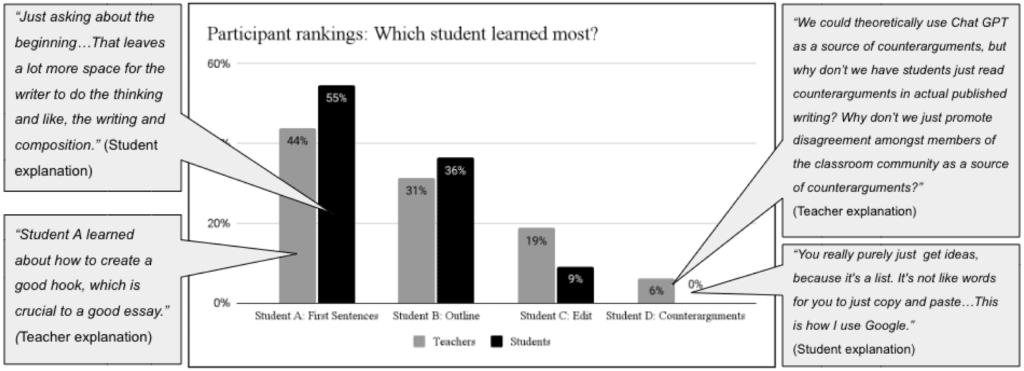

Our analysis revealed a range of views about what constituted cheating and learning, both within and between groups. For example, about half of our participants ranked Student A (who asked for first sentences) as learning the most, but about a third ranked Student B (who asked for an outline) as learning the most. Figure 1 below shows how participants ranked which student learned the most, along with explanations they provided.

Figure 1: Participants’ rankings and explanations of which student learned the most

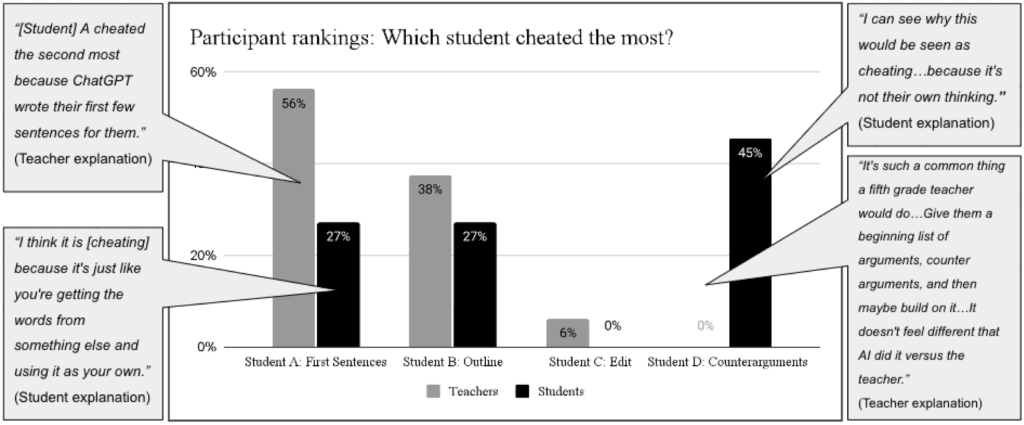

We found even more variation when we asked which student cheated the most. For example, none of the teachers thought that Student D (who asked ChatGPT to suggest counterarguments) cheated the most, while nearly half of the students did. Additionally, while nearly half of the teachers thought that Student A (who asked for possible first sentences) learned the most, the other half thought that student cheated the most. These diverging rankings and their explanations are summarized in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Participants’ rankings and explanations of which student cheated the most

Differences in views were grounded in three recurring tensions

We identified three recurring tensions that accounted for most of our participants’ differing opinions.

Tension 1: Using ChatGPT as a shortcut versus as a scaffold

Whether participants thought the student learned or cheated frequently depended on whether they viewed ChatGPT as a shortcut that did the thinking for the student or as a scaffold that the student could learn from. One teacher summed up both perspectives in this tension, explaining:

The student asked ChatGPT to provide counterarguments. On the one hand, that actually is forcing the student to think of arguments or rebuttals to the counterargument, which is learning, right? But if that student then copies and pastes the counterargument from ChatGPT into their essay, and doesn’t acknowledge where the counterargument is coming from, or tries to pass it off as a hypothetical counterargument that their own brain thought of, then that becomes ‘cheaty.’

Tension 2: Using ChatGPT to generate ideas versus language

Another tension involved whether the student used ChatGPT to generate ideas or to generate specific language. This tension called into question whether participants viewed writing broadly (as a process of brainstorming, organizing, revising, etc.) or narrowly (as the act of composing). One teacher explained:

What do we consider to be more ‘cheaty’? Is it taking someone else’s idea or taking someone else’s words or language? I don’t really know the answer. I’m more inclined to have kids come up with their own ideas. But then sometimes you need to give them an idea as a scaffold.

Tension 3: Getting support from ChatGPT versus analogous support from other sources

In evaluating how much each student learned or cheated, participants frequently asked how students might typically seek help from accepted non-AI resources. Students named similarities in instruction and tools:

“I feel like this is just like asking a teacher like and teachers give you ideas like this…I think this is optimal learning.”

“So…kind of like how you have Grammarly, it’s kind of like that but using ChatGPT”

Teachers reflected on ChatGPT’s similarity to routine instructional strategies:

“The very common thing a fifth grade teacher would do would [be to] give them a beginning list of kind of arguments, counterarguments, and then maybe build on it…It doesn’t feel different if AI did it versus the teacher.”

Recommendations for educators

These findings illustrate a more complicated picture of cheating and learning with AI than mainstream discourse would suggest. Based on these findings, we recommend a few next steps for educators.

- Prioritize process over product: AI makes it more important than ever to make students’ thinking visible at every step of the learning process. Teachers should consider shifting away from writing as the sole form of assessment and toward a model of writing as a mode of thinking.

- Be clear and transparent about learning goals: Before deciding whether a particular use of AI supports learning goals, teachers should be clear and transparent about what those learning goals are. Using AI to generate an outline may be a legitimate scaffold for learning to write a multi-page research report, but it may be a counterproductive shortcut if the goal is learning to organize an extended piece of writing.

- Dialogue with students about responsible AI use: Our study suggests that teachers and students hold a variety of views about responsible AI use. Rather than making assumptions, teachers should be in dialogue with students and co-construct norms around responsible AI use. Many of the teachers we have worked with have done so by using the ranking activity in their classes.

To be clear, teachers’ worries about cheating and learning loss are completely valid. AI tools make it very simple for students to shortcut their learning, intentionally or not. This is all the more reason to explicitly teach students not only what they cannot do but also what they can do with AI. The ability to understand, evaluate, and use AI tools is an increasingly important component of basic literacy in the AI era. Ensuring that all students have access to these skills is one of the most important equity issues of our generation.

Additional CoSN Resources: https://www.cosn.org/ai/

AUTHORS:

Chris Mah, Doctoral Student, Stanford University Graduate School of Education (CA)

Hillary Walker, Director, Bay Area Writing Project (CA)

Chris Mah is a PhD candidate at the Stanford Graduate School of Education. His research focuses on AI literacy, teacher education, and writing. He is a former high school English teacher.

Hillary Walker is Director of the Bay Area Writing Project. She also teaches Ethnic Studies in high school and college. Her research interests include professional learning for educators and writing practices in classrooms.

Published on: May 6, 2025

CoSN is vendor neutral and does not endorse products or services. Any mention of a specific solution is for contextual purposes.